Through a Glass Darkly

Gabriele Riccobono • 3 min read

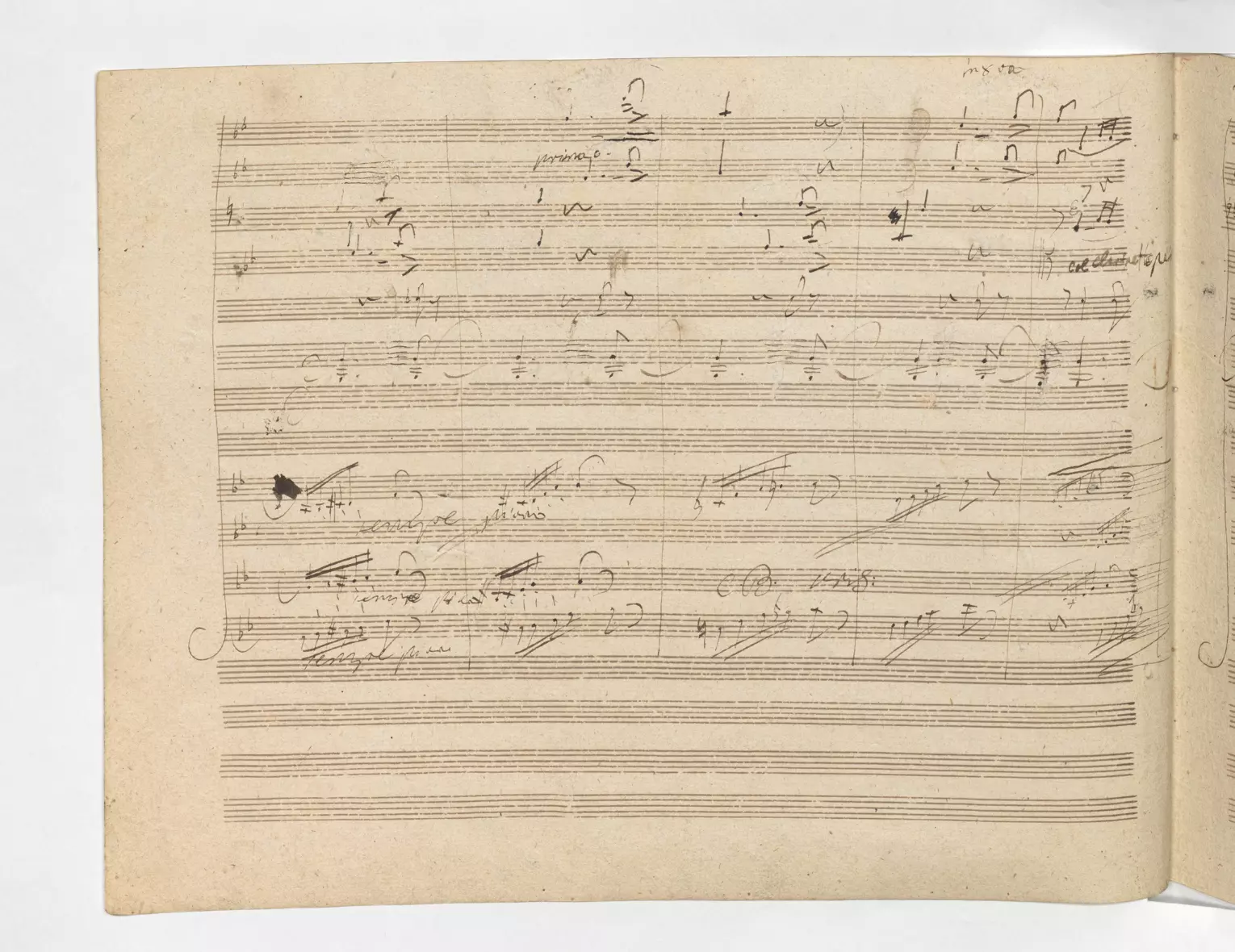

Millions of musicians develop their interpretations using scores edited by hands other than that of the composer.

Consider scholarly or performing editions: they present a version of the work defined according to specific editorial criteria, which can range from an ideal of fidelity to the composer’s intention to its exact opposite. Despite undeniable advantages, such critical mediation systematically entails an authenticity defect (the lack of a direct relationship between work and performer) and thus the risk of musicians unintentionally interpreting someone else’s interpretation.

The reader may recall a case pointed out by Jonathan Del Mar a few years ago. In his edition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (Bärenreiter-Verlag, 1996), the distinguished British scholar restored a D that had been printed (and played) as B-flat for decades, redefining the melodic profile of the second thematic group of the Allegro (bar 81). Del Mar’s correction is strictly based on the primary sources, which are all consistent on this point. In contrast, from 1862 onwards, almost all editions introduced the B-flat for reasons of internal symmetry, often without highlighting it in any way. So, an editorial revision has replaced the composer’s original text, precluding many musicians from choosing for themselves what to perform.

Were conductors like Toscanini, Furtwängler, or Karajan aware that Beethoven did not write the B-flat? Although the D can still be found in some secondary sources (such as Wagner’s copy and piano transcription or Grove’s Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies), the writer does not know of any recording featuring the D made before Del Mar’s edition. Today, with more information, some are considering it again, while others have decided to keep the B-flat. Either way, the important thing is to choose intentionally. Bernstein, for example, was probably aware of the revision: a 1962 photo from the Leon Levy Digital Archive shows him with an exemplar of the first edition of the Symphony.

Of course, one might say that the ideal critical mediation is the one that does not mediate at all — that is, the one that seeks to witness the original texts. Though, there are as many editorial criteria as there are editors, and, beyond utopia, no edition can entirely render the irreducible complexity of the primary sources.

The best solution for musicians would be to combine scholarly and performing editions with the personal observation of sources, or at least their digital versions, which are increasingly available today. (For instance, those who would like to examine the Berlin autograph score of the Ninth Symphony will find accurate digitisation on the Staatsbibliothek website).

This way, more informed decisions can be made, and unexpected possibilities (discarded or not covered by the editor) might open up. One will also be able to understand and appreciate better both the composer’s and the editors’ perspectives — similarly to what happens with parallel text editions of literary masterpieces. After all, anyone who reads Exercices de style in Umberto Eco’s translation without accompanying it with the original thus only knows one masterpiece instead of two.

Milan, 12 August 2022